这位写了红遍全球的《一个叫欧维的男人决定去死》的80后作家又出新书了。

三年前读《欧维》(四川文艺出版社宁蒙译版)的时候就被Fredrik Backman有趣的文风和特别的叙事风格深深吸引,他擅长用一种幽默和生动的文笔来写你平时提也不敢提的内心深处细微的情感,每一页都有笑又有泪,用一种有些戏谑的方式来写焦虑与生死。

我一般对于所谓的“电影原著”是不屑一顾的。如果一部我已读过且喜欢的小说被改编成了影视作品,我通常都会兴致勃勃去看。而一旦顺序反了过来,却往往让我排斥:一部影视作品先走红,我无论看过还是没看过,都不会再对阅读原著产生任何兴趣。

但是《欧维》不一样。电影的大获成功并没有让我失去读书的兴趣,虽然我也只是随手翻出这本书来读,却被大大地惊艳到。

于是我作为一个平时很少关注书讯的人,在某天偶然看到Backman又出了新作,自然在兴奋之余果断下单买了下来。熟悉我的人知道我除了为了讨签名之外极少在美国买纸书,一般都是读电子版,但是这本值得。(我也要等到Backman来美国开见面会的时候去讨签名呢)

一周的时间内读完了这本《Anxious People》,被每一页里的每一句的温柔包围,笑到岔气,也痛痛快快哭过几次。

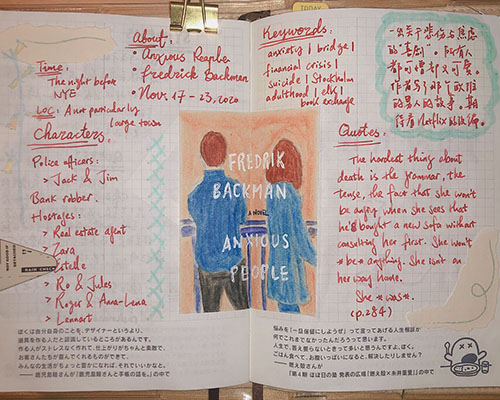

关于这本书的几个关键词:金融危机、焦虑、抢劫、Stockholm、自杀、死亡、被迫长大成人承担责任。

某一个新年夜的前一天,一位带着面具的劫匪持枪冲进一家银行打劫。失败之后(这碰巧是一家“无现金银行”)劫匪落荒而逃,跑上了一幢公寓楼的顶楼,撞见了一群来看房的租客们。就这样,这出打劫未遂的闹剧演变成了挟持人质的闹剧。

被挟持的人质有:

- 一位从未在书中被提到名字的女房产经纪人。

- Zara: 五十多岁的女银行家,因为失眠而去看心理医生,腰缠万贯却以“看中产阶级买房”为乐,只因这样能让她体验另一种人生。

- Anna-Lena & Roger: 一对退休了的夫妻,为了让生活有些奔头,不断购置新房、装修完善以后再卖掉,平时去最多的地方是宜家。

- Julia “Jules” & Ro: 一对从Stockholm来的年轻女同性恋伴侣,Jules怀了孕,两人在寻找以后和小孩共同生活的家。

- Estelle: 78岁的老太太,一个不太有存在感的人。(却在书中说了很多很多的话)

- Lennart: 自称是位“演员”,受雇佣去做荒唐事来搅乱别人的生活,以此为生。

每个出场的人物都说了很多话、有很多的情绪和很多的故事,这当然也是Backman最擅长展开来写的。这样看似闹剧的背后所有人都有深深的焦虑,也其实都有颗温柔的内心需要被唤醒。看着书里人物的命运被一点点串在一起,看着他们无论年长年少,在成长的过程中都有各自的困惑,谁又能说“成长的烦恼”只能用在青少年身上呢?这个世界对谁还不是一样的陌生,没有人天生就会应对生活的。所以你所有的焦虑都情有可原,拥抱焦虑,走得出、走不出最后都靠你自己,但无论怎样的结果都是可以的,因为这都不是你的错。

最后再说一句,听说网飞过一阵子要上线以这本小说改编的电视剧,定位是”喜剧“。我也很好奇,这样一个笑中带泪的故事,又会变诠释成个什么样子呢。

摘录:

Because there’s such an unbelievable amount that we’re all supposed to be able to cope with these days. You’re supposed to have a job, and somewhere to live, and a family, and you’re supposed to pay taxes and have clean underwear and remember the password to your damn Wi-Fi. Some of us never manage to get the chaos under control, so our lives simply carry on, the world spinning through space at two million miles an hour while we bounce about on its surface like so many lost socks. (p1)

That was a parent’s job: to provide shoulders. Shoulder for you children to sit on when they’re little so they can see the world, then stand on when they get older so they can reach the clouds, and sometimes lean against whenever they stumble and feel unsure. They trust us, which is a crushing responsibility, because they haven’t yet realized that we don’t actually know what we’re doing. So the man did what we all do: he pretended he knew. (p22)

The bank robber was standing in the center of the apartment, surrounded by Stockholmers, both figurative and literal. “Stockholm” is, after all, an expression more than it is a place, both for men like Roger and for most of the rest of us, just a symbolic word to denote all the irritating people who get in the way of our happiness. People who think they’re better than us. Bankers who say no when we apply for a loan, psychologists who ask questions when we only want sleeping pills, old men who steal the apartments we want to renovate, rabbits who steal our wives. Everyone has Stockholmers in their life, even people from Stockholm have their own Stockholmers, only to them it’s “people who live in New York” or “politicians in Brussels,” or other people from some other place where people seem to think that they’re better than the Stockholmers think they are. (p156)

The hardest thing about death is the grammar, the tense, the fact that she won’t be angry when she sees that he’s bought a new sofa without consulting her first. She won’t be anything. She isn’t on her way home. She was. (p284)